RESEARCHERS PILOT AUTISM TRAINING FOR EMERGENCY RESPONDERS

Lights and sirens can be a nightmare for people with autism. UVA researchers are helping train responders to ease those fears. (Illustration by Emily Faith Morgan, University Communications)

It can be a recipe for trouble.

People with autism are seven times more likely than the general population to encounter emergency responders, but the common elements of an emergency response – flashing lights, loud sirens, strangers asking questions – are often a nightmare for people with sensory processing challenges.

People with autism – a neurodevelopmental condition that affects communication, social skills and sensory processing – often need help from emergency personnel because of co-occurring medical and mental health conditions and behaviors like self-injury and wandering. One in five children on the autism spectrum will have an encounter with law enforcement by the time they are 21.

Yet, most first responders receive no training on how to interact with and support autistic individuals and high turnover rates among first responders decrease the likelihood that learning will be maintained over time, said Rose Nevill with the University of Virginia’s Supporting Transformative Autism Research (STAR) initiative.

As the head of STAR’s Autism Research Core, Nevill supports autism research across Grounds and works closely with a large network of families and individuals with autism in the local community and throughout Virginia.

“What we’ve learned through this work is that, largely, families are calling 911 as an absolute last resort because they’re afraid of what’s going to happen,” she said.

A new training for first responders, developed by STAR and piloted earlier this month with local emergency medical technicians, including many UVA students, aims to change that.

Developing better autism training

The training was years in the making. Building on work from the Charlottesville Autism Action Group, a local advocacy organization, STAR organized a focus group in 2019 that identified first responder training as a priority.

STAR partnered with the Thomas Jefferson EMS Council, or TJEMS, an independent organization that provides training and coordination for EMS agencies in Charlottesville and surrounding counties. They worked together to secure grant funding to develop an extensive, interactive training.

Peppy Winchel, executive director of TJEMS, said first responders make quick decisions with limited information in high-stress environments. With vulnerable populations, such as the autistic community, it’s even more important to be trained to accurately assess the situation and deescalate when needed.

Winchel has a background in public health and emergency management, served as a combat medic in the US Army and taught science to kids with learning disorders. He has a particular passion for serving vulnerable communities and always has an eye on the bigger picture.

He said a single interaction with a medical provider can have long-lasting impacts. “As you’re interacting with patients, they’re going to take that experience and extrapolate to their future experiences with healthcare,” he said.

As the training began to take shape, the STAR team held focus groups and interviews with first responders, family members, caregivers, autistic adults and others with a stake in the outcomes.

“I was expecting them to have very different perspectives on what first responders should know,” Nevill said. “But there was so much overlap across groups. They all really seem to want better communication and collaboration.”

Piloting with local EMTs

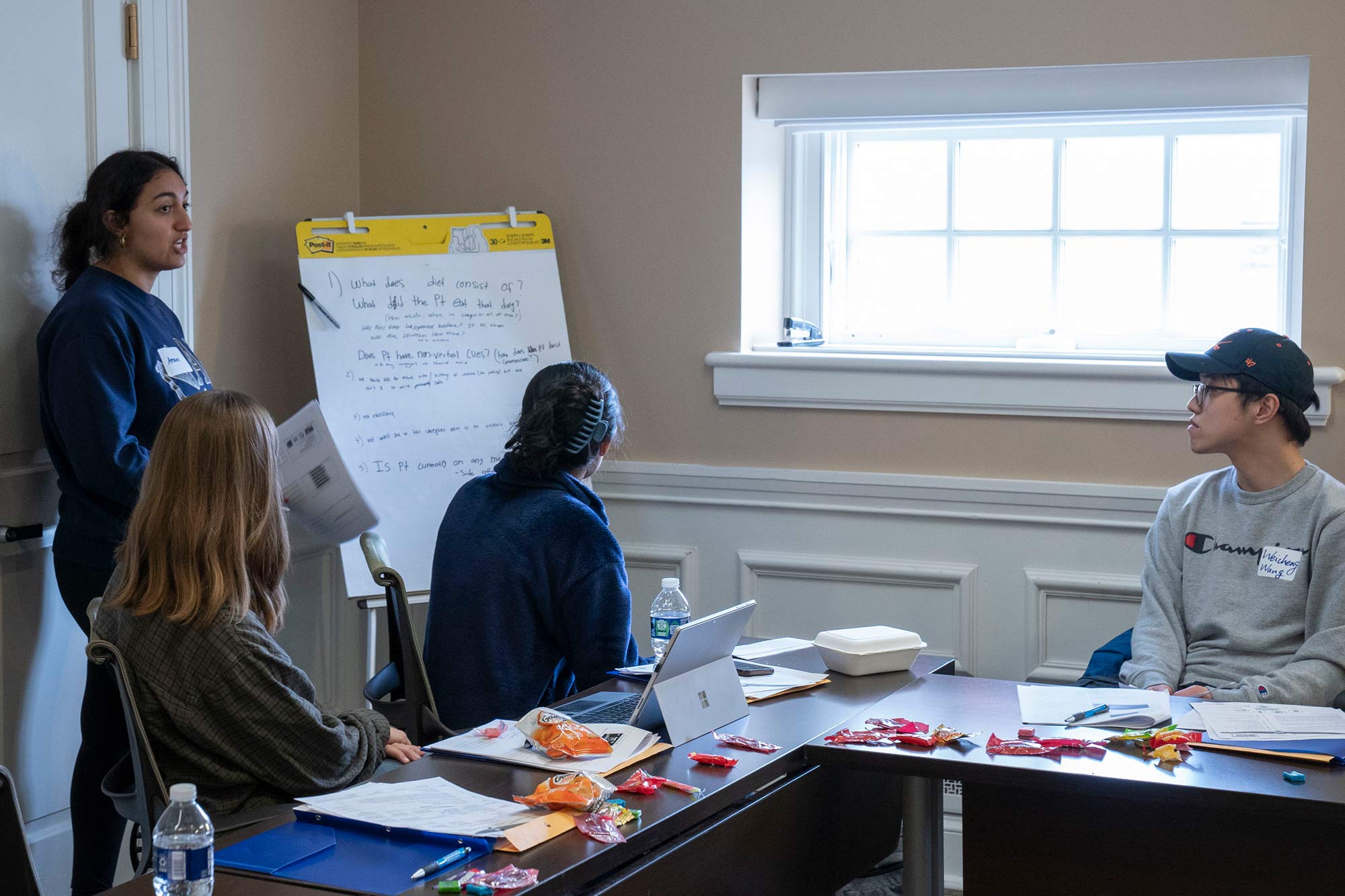

The four-hour autism training is an interactive mixture of lecture and hands-on activities. Earlier this month, Winchel and Nevill led several sessions on Grounds to pilot the training with local EMTs, many of them UVA students.

Luke Anzaldi, a fourth-year politics and biology double-major, began working as an EMT with Lake Monticello Rescue Squad in August.

“Even before the training, I certainly had an awareness of how interactions with first responders and people with autism can go south. I’ve seen it on the news and on social media,” he said. “I don’t have any close personal relationships with people with autism, so I was definitely interested in understanding how those interactions should go.”

Participants learned to recognize common signs of autism, such as repeated motor movements called “stimming,” or difficulty with eye contact, to help them differentiate it from other conditions. Nevill also reviewed reasons that autistic people are likely to encounter emergency responders and frequent co-occurring medical conditions.

Then, they discussed how to improve interactions. Using the acronym SOCIAL, Nevill focused on six strategies for responders; be aware of sensory needs; operate as a team with one main communicator; use calm and confident communication; use the person’s interests as tools; involve the person’s parent or advocate; and loop back with the person, family and agencies.

“We’ve built in a lot of roleplays and practice opportunities, and we’re really trying to drive home these six key things to remember when you go onto the scene,” Nevill said.

Like many student first responders, Abby Burke, a fourth-year biology major, began working as an EMT to gain some hands-on experience in a medical setting.

Burke and Anzaldi both said the scenarios were the most helpful part of the training. “I loved being able to think out loud with my team about how we’d realistically incorporate all of the training in order to provide the best care for our patients,” Burke said.

“When people call us, they already are having their worst day,” she added. “They are often really vulnerable, really uncomfortable. So it was great to have this class where we could learn how to make the experience less scary.”

Refining and expanding training

The team plans to take the training to all branches of emergency response across the state and expand the training to other neurodevelopmental disorders such as dementia. They also plan community sessions with the local autism community and seek ways to improve the training.

“We’ve developed a resource that we hope is adapted into other communities,” Winchel said. “That’s what I’d really like to see happen, that it’s rolled out and adapted and really becomes its own program.”

A paramedic with 25 years experience, Serena Imel said she still learned new information during the training. She also had personal reasons for attending as she has a daughter on the spectrum.

“I felt like [the training] really addressed the main challenges that we face when dealing with people in the autistic community. And I like that it highlighted the dangers that people with autism face when interacting with emergency services,” she said.

“I just really appreciated the class and I’m hoping that we can branch out and get it in [other] departments and start spreading the word.”

This work was conducted with the support of the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under Award Numbers UL1TR003015 and KL2TR003016, UVA School of Education and Human Development, and UVA Jefferson Trust.